Q&A: D.C. Vito of The Lamp on Fake News and Media Literacy

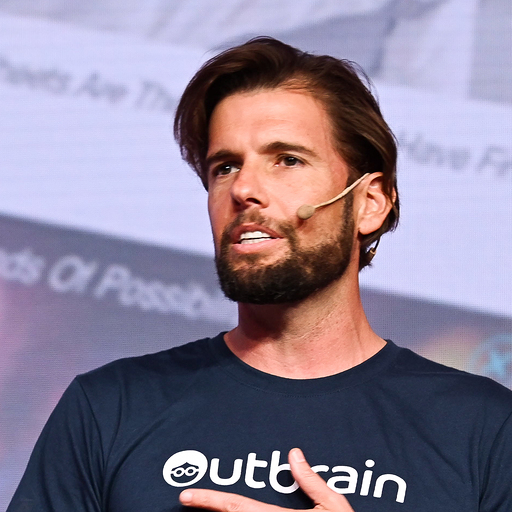

In my recent post on the topic of fake news I covered the difficulties and importance of being able to distinguish what is real news versus what is not and was interested to get a perspective from one of the industry’s leading experts. This week, I took time out to chat with The Lamp’s Executive Director, D.C. Vito, about his organization’s mission to help young people understand media, make their own media—and use these new skills to challenge harmful, misleading, and untrue media messages.

Vito explains some of the biggest challenges in getting young people to understand media biases and spot fake news. “Unfortunately, even though it’s often stated that youth are ‘digital natives,’ this is misleading,” he says. “Yes, they’ve never known a world without the internet. But, I’ve never known a world without cars and roads, and I certainly needed to be trained how to operate a car and navigate the roads before I was set free. So, all youth need to be taught what are the various media that comes to them through their devices.”

Read my interview with him to understand some of the key things you should consider and learn more about his organization.

KP: Can you tell me a little more about LAMP and why you decided to start this organization?

DCV: We are an organization whose main mission is help young people understand media, help them learn how to make their own media, and ultimately to use these skills to challenge harmful, misleading and untrue messages. From the beginning, we have had a civic focus, helping youth understand they have the opportunity these days to challenge and talk back to media they find irresponsible. As a young person myself, I was very civically active, volunteering on my first Presidential campaign when I was 13. Even though I couldn’t vote, I saw the importance of making sure the youth voice was part of the dialog as we were deciding what direction our democracy was going. After all, it’s youth who inherit all of the systems and structures that are put in place by the political process. Starting around 2006, I noticed that media play a massive role in shaping how we see the world, how we see ourselves, and certainly how we come to understand democracy. In having conversations with folks about this, I was introduced to our co-Founder, Professor Katherine Fry at Brooklyn College. We got together and decided to start a non-profit that would work in communities (“the trenches” as we put it), and help them gain these vital media literacies.

KP: What are some of the specific ways you work with kids to teach them media literacy?

DCV: Our work revolves around four tracks: Commercials and Advertising; News and Reporting; Exploring Images and Video; and Digital Media. Everything we do is hands-on, so our students are immediately constructing the various media artifacts, to gain the awareness that all media are constructions and not organic items that just blossom, untouched by someone else. At every step of the program, we are infusing critical thinking about media, encouraging them to explore their curiosity and ask questions about what they encounter.

KP: With the proliferation of digital media and early exposure to it, are you noticing that kids are more media literate or less so these days? What, in your opinion, is the biggest challenge in getting them to understand media biases or spot misleading news?

DCV: Unfortunately, even though it’s often stated that youth are “digital natives,” this is misleading. Yes, they’ve never known a world without the Internet. But, I’ve never known a world without cars and roads, and I certainly needed to be trained how to operate a car and navigate the roads before I was set free. So, all youth need to be taught what are the various media that comes to them through their devices.

Why are social media sites “free”? Is my experience on social media the same as my siblings? My parents? How much time should I spend on social media? What is built into social media that makes them so tantalizing to consume? (just some of the questions)

The biggest challenge is getting them to slow down before they share. The first way to understand if something is misleading is find other sources before you share. Too often, we (yes, even adults) will share something before we’ve fully read it because it confirms what we want to believe, but also because social media are set up to reward us for the number of likes, +1, hearts our posts get. We are incentivized to share rapidly, and check back-in often to see if our posts were popular with our friends/followers.

KP: Can you tell me about some of your brand partnerships and programs?

DCV: We’ve had some great partnerships with companies. Google has funded our programs for several years, which has been an exciting thing both for our organization but also for our students who often get to take field trips to Google as part of the program. We’ve also had a long-term partnership with Mozilla, who has funded us to do a lot of different, innovative and exciting projects. They have been a big sponsor of our MediaBreaker/Studios tool, which is an online tool that allows students and educators to re-edit video with the intent of creating critical, multimedia essays.

KP: What’s your point of view on fake news and misleading news? How do you think people become better at spotting it?

DCV: Most importantly, whenever I get the chance, I want people to know that “Fake News” isn’t new at all. Since the founding of this country, there have been fake stories planted in newspapers. The thing that IS new is that we get to challenge it now with all these digital tools and social media. I always say the best fact checker is time. For instance, after a tragic event, the first reports that come out are most often inaccurate as the capture of information is messy and chaotic. Giving a story time to brew and develop, and for the facts to become clear is the best way to handle news. And if the headline of a story drives up some dramatic reaction, you can most often guess that it is some form of inflammatory misinformation. News that’s trustworthy and fact-based rarely aims to elicit stark, emotional responses.

KP: What would be your three best tips for people to consider?

DCV: How often am I checking my phone throughout the day? Just take a count. Consider turning your phone off at night, or leaving it outside the bedroom. Find ways to limit the amount of breaking news reports, news flashes or click-bait that you encounter. The more information we are inundated with, the less likely we are able to exercise our critical thinking about it. That’s how “fake news”/misinformation works. It thrives on us turning off our reasoning skills, and wants us to just be emotional (this is also how commercials work too).